Auld Lang Syne

For all my old BSU friends, I've been meaning to get this digitized for years, but didn't have the means to get it from VHS to DVD until recently. Enjoy, and Happy New Year!

For all my old BSU friends, I've been meaning to get this digitized for years, but didn't have the means to get it from VHS to DVD until recently. Enjoy, and Happy New Year!

What do I mean when I say an "inversion of power'?

A brief survey of history reveals that the structures humans have produced (sometimes in God’s name) tend to serve self-satisfaction through oppression, abuse, and privilege. Such an exercise in power inevitably leads towards the oppressed rising up and demanding justice through the very means once used against them. I could go on and on about the natural urge for dominance and fulfillment, and the cycle of violence that creates, but ultimately Gandhi was right when he said an eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind. And, I might add, still angry.

In contrast to human structures, Jesus’ way of thinking about power, love, freedom, and humanity was so radical to those around him that he said one had to be "born again" to understand it. In fact, being born again is a prerequisite for entering into the "kingdom of God".

In earthly kingdoms, people sacrifice freedom to make the king rich and powerful in exchange for protection and provision. But, by and large, the kingdom of God is an inversion of this. In an earthly kingdom, commoners are often forced to give their lives to protect the king’s son. In the kingdom of God, the king’s son willingly gives up his life to protect the people. In earthly kingdoms, people pay taxes so that the king can have more power. In the kingdom of God, the king gives of his infinite excess so that the people can become rich.

This biblical intuition of the inversion of power can be seen throughout the old testament (how often was the rule of primogeniture reversed?), culminating in the beatitudes, the apostles, and the very life of Jesus given for us all.

Here is my point - the inversion of power isn’t just about the weak become powerful, though it is about that, too. The inversion of power is also about giving away power out of a desire for something better than primal self-satisfaction. Power tends to seek more power so that the powerful can get good things. The inversion of power seeks to give power away for the benefit of everyone.

So, how does this relate to forgiveness, especially when the flow of forgiveness seems to be one-way?

I don't want to speak for others, but there have been times in my life when I was not able to forgive until I realized the turmoil within those who harmed me. And, as time passed and my days were colored by God, I realized that He had made me powerful. Not some worldly power that derives its strength from taking things from others, or some physical show of force that commands attention, but a divine power that is able to give itself away out of excess. For me, this kind of power has become emotional stability, spiritual purpose, and hope for the future to the point where I could risk my very well-being because I am so blessed. I don’t want to take back what people, in their weakness, felt compelled to steal from me. Instead, forgiveness for me has become a time of mercy in which I mourn over the depths of weakness and confusion that lead to others taking things from me under the guise of power, but which I could now forgive out of my excess. However, this process takes time.

For those individuals who have been raped or molested, or for those peoples who are systematically oppressed, I wonder how long the process of forgiveness might take. How long until a woman can feel powerful enough to forgive the debt that the rapist incurred? Again, not power rooted in taking from others, but power rooted in being filled to excess. How long until those who have been oppressed for many generations can find the internal fortitude to forgive their oppressors?

I don’t have good answers to these questions. Maybe, on some tangible level, restitution makes sense in the process of forgiveness. Maybe counseling makes sense. Maybe being separated from the actual person and place forever is the only way to regain a permanent sense of well-being out of which forgiveness can spring. I don’t know how long is too long to wait for true forgiveness. But I’ve become convinced that the healing embrace that will cure the world happens when people come to grips with the inversion of power demonstrated to us by Christ, and instead of using their resources to take, use their resources to love.

"Hatred stirs up dissension, but love covers over all wrongs."

"So let us consider how we may spur one another on towards love..."

Posted by Benjamin at 10:28 AM Labels: forgiveness, theology

Part II of the forgiveness post is taking me longer to articulate than I expected. Sometimes getting things from head and heart to paper (or blog) is like giving birth. Things tear and bleed and hurt.

In any case, while I get an epidural, here is a blast from the very distant past. I journaled a bit when I was a teenager, and I believe the following snippet was written when I was 17 or so. My actual thoughts have shifted quite a bit since writing this (I'm almost twice as old!), so don't go commenting as if this something I accept today. Since a lot of the conversation I've been hearing lately has been about the journey of faith, I thought I would look into mine a bit more. As far as I remember, this is my first written attempt at articulating the relation of God to creation, and the beginning of my rejection of creation ex nihilo for creation ex dei.

Does anyone see any glaring problems in the following framework?

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

...which does bring up another good point to pursue. Why is Satan still here? Why is it that God can destroy the entirety of civilization with Noah with the justification that they are evil and have turned from Him, yet not destroy Satan himself? I think that we have to look at the way the universe is set up to explain.

Physics tells us that all things are constant in the universe. Nothing is either created or destroyed. Matter is always conserved in a reaction; energy is always conserved in a process; momentum is always conserved in a collision. Granted, there are times when matter can be converted to energy and vise versa, but the rule is that all things are conserved. No exceptions. When we die, our bodies decay and rot and become life again while our souls soar towards the heavens and eternity. Everything is conserved. Almost as if God is not willing to destroy anything that He as created.

Which makes sense to me. God created the universe, and after each step said “It is good,”. Why would he destroy something that He Himself has deemed good? He may destroy, like He did

Satan, however, is a different story. Satan has a spirit of destruction within him. Satan destroyed the bond between God and Adam in the Garden of Eden. Satan destroyed the bond between brothers when Cain killed Abel. Satan destroyed the connection between man and woman with lust and perversion. And Satan destroys the bond between me and God. The times I feel furthest from God, have the craving and desire to destroy. Not only to destroy, but to obliterate from existence, so that nothing remains of the object of my anger. Satan is a destroyer.

Which may, in fact, be the definition of sin to God. The act of destruction. God could no longer be with Adam because Adam had taken part in the destruction of something God had created. And this continues. God cannot be with man because man has destroyed something that He as created, and that is an abomination to Him. And God despises Satan because Satan is the Destroyer. Probably, that is what separated God and Lucifer in the first place. God created Something, and Lucifer thought that the Something would be best destroyed. God refused to destroy the Something, so Lucifer tried to go behind God’s back and destroy it. Hence the separation of God and Lucifer. Other angels thought that Lucifer had the right idea, that destruction of the Something was the way to go, so they were cast out of heaven also.

Whether or not Lucifer succeeded in destroying the Something is irrelevant, and whether or not Satan has the ability to create is fairly irrelevant also. The fact is that Satan destroyed, if not the Something, then the relationship he had with God. And the destruction of what God had created was reprehensible.

God still refuses to destroy, which is fine by me. Even in the End there will be no destruction. Except for the destruction of evil, which is something that God never created anyway. All of our souls will live eternally, either with God or in the Lake of Fire, and Satan and his henchmen will burn in the Lake of Fire as well. And what an amazing end for them. They will be conserved, these spirits that burn but are never consumed, yet the evil that caused them to destroy will be burned away forever, leaving only the glorious things that God has created.

I'm intrigued by the concept of forgiveness.

Upon occasion, I get to teach various groups at my church, which is astounding if you really think about it. A couple of weeks ago, I was asked to teach in a class about some of the examples Jesus gave for good relationships.

Jesus taught many things, and one of them was forgiveness. He taught that people will be forgiven to the extent that they forgive, which encompasses both quality (from your heart), and quanity (seventy times seven). I won't go into all of it here, but the the divine call to forgive is powerful and vast.

Indubitably, Christians are called to forgive. This often translates into a Christian imperative that a Christian must forgive no matter what, or they aren't being a good Christian. This leads to all sorts of strange behaviors that parade under the guise of "forgiveness", but are really nothing more than faking it. Sometimes, it leads to a sort of forced servitude in which the forgiver submits to the forgiven in an attempt to follow Christ's example. This is cheap forgiveness.

This sort of forgiveness enables those who are powerful to abuse those who are less powerful. With the kind of forgiveness that must be applied no matter what, those who are beaten, shamed, and violated (emtionally, physically, spiritually, or otherwise) by those who are more powerful are prevented from taking action against those who are stronger. Such a system enables oppression, and ignores the Biblical mandate to fight against injustice - to protect the downtrodden and weak, and to pursue justice for all people. One could even argue that such a view of forgiveness erodes the legal system, since forgiveness must be applied seventy-times-seven no matter the crime. Should our call to forgive really supersede our call to justice, and protection of the oppressed?

As I've groped for a better understanding of the complex beast that is forgiveness, Matthew 18:21-35 continues to stick in my mind. In this passage, Jesus is asked about forgiveness, and he responds with telling a story about a man who wanted to settle his accounts with his servants. One servant owed the king more than he could ever pay, and so the king, in his mercy, let the servant go. This first servant, in turn, went to a servant coworker that owed him just a few dollars and had him thrown in jail for not paying the debt. When the king found that his servant had done such a thing, he was livid, and had the first servant thrown in jail and tortured until he could pay the unpayable debt. The story ends with an admonition from Jesus:

"This is how my heavenly Father will treat each of you unless you forgive your brother from your heart."

It seems to me that something is happening in this parable that we often don't think about. In every instance of forgiveness in this parable, forgiveness flows from one more powerful to one less powerful. The king, who is the ultimate authority, forgives his servant. The servant, who has legal power over his debtors, is in turn supposed to forgive his debtors. There is no speaking of the debtor, who is the one in danger of being oppressed, doing any forgiving.

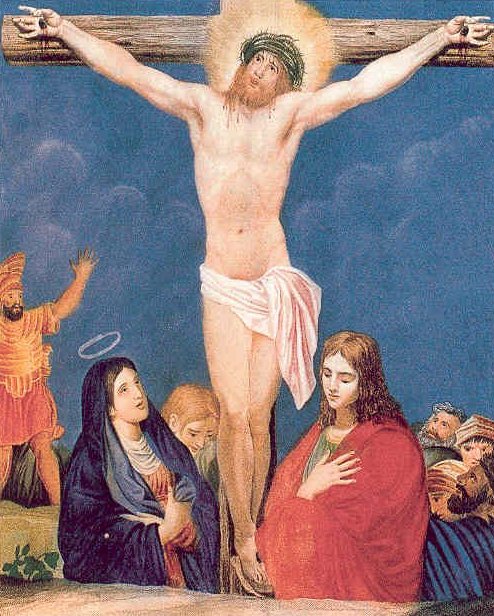

But if only the powerful do the forgiving, then what do we make out of Jesus being crucified, or of Stephen being stoned, or of the beatings suffered by Paul, or of the persecution of the church? Doesn't it seem that these were beaten and oppressed by ones more powerful, and yet forgave anyway?

As I reflect upon the power tactics of Jesus, I'm not so sure he was killed by those more powerful. Those who are the greatest in Jesus' kingdom are those who are the least, those who come to him as a child, those who give up their life to save it. Jesus' example is that real power is the inversion of power. Power occurs not when you find satisfaction on the intoxication of being above others, but instead satisfaction is found in the healing embrace of God, who welcomes us into a new way of living no matter our previous offense.

So, who was greater - the Son of God who could call a host of angels, or those who thought nailing him to a tree was the best way to get rid of him? Who was greater - Stephen, who looked into heaven and saw the Son of God smiling back at him, or those who picked up sticks and rocks in a blind rage? Who was greater - Paul, who found the worth of his being in the affirmations of Christ, or those who hated him for the message he preached?

Biblically, the direction of flow is a heavy theme of forgiveness. In every case I've ever come across, the more powerful one always forgives the less powerful. In every case, the oppressed cry out, and the powerful forgive. Never to do the oppressed, violated, or abused forgive the powerful unless the powerful are first humbled and the oppressed gain power over them. The flow seems to be only one-way.

I've realized that most people find this view of forgiveness radical and strange - the Sunday School class I taught sure thought it was strange. What do you think about it? Can you think of a Biblical example of forgiveness that does not come from the one who is more powerful? What is the Biblical intuition of power?

Posted by Benjamin at 12:37 PM Labels: forgiveness, theology

While I wasn't as enthralled with the students as I hoped, I enjoyed almost every one of my professors. Some where touchy-feely, some were analytical, some were funny, and some were as serious as a heart attack. Although some were not very good teachers, they were all well trained and really seemed to know their stuff when pressed, with more than one being what I call 'stone-cold brilliant' - a designation I don't use lightly.

As I went through my classes, I found myself consistently wondering why I had never heard the gospel presented in the ways it was in Seminary. One professor (one of my favorites) walked in on the first day of class and said, "I have good news and I have bad news. The bad news is that the god you were taught about as you grew up doesn't exist. He's a myth. The good news is that the God of the Bible does exist."

He was right. As I went through seminary, learned about the formation of the biblical canon, learned about textual criticism, learned about church history, and psychology, and hermeneutics, and theology through the ages, it was like scales were falling from my eyes. The journey can't really be described, but it was life-shifting. For me, this shift was in a good direction, for some others, the shift knocked them off their moorings.

The question I kept asking myself, again and again, is why this altered understanding of the Christian faith and of God doesn't filter down to congregations. The answer has to do with what that professor told us on the first day of class.

People don't like it when the god of their childhood is in danger of being altered. People don't like it when they find the very faith that they have clung to - the foundation of their thinking - is actually balanced precariously on the edge of a cliff. People don't like it when they have to realize that our scientific understanding of the world actually should change the ways in which we think about God, reality, and the Bible. People get scared when they are taught about the real nature of truth, or about the real history of the Christian scriptures.

Here's an example - one of the best New Testament textual critics in the world, Michael Holmes, works at Bethel University. (Textual criticism refers to reconstructing the original scripture, which no longer exists, from the many variant scripture documents that still exist.) He was a guest lecturer in one of my Greek classes, and walked us through several text critical issues in rapid fire succession. For someone like me, who saw the Bible as a bulletproof document with no problems whatsoever, these examples were devastating. I felt my world starting to shift. Others in the class must have felt the same way because at least a few, men and women alike, walked out during the middle of class, sobbing. Perhaps theirs wasn't a shift as much as a collapse.

Now, Dr. Holmes is a very strong Christian, very loving and kind, and very good at his job. This scenario is not entirely his fault. But the reality is that Biblical inerrancy like I was taught in church is problematic. The type and extent of these problems aren't well understood (if at all) by most laypeople, yet these issues cannot be historically disputed by any reasonable individual. Can you imagine the response of a congregation to teaching that drives seminary students from class with tears streaming down their face? Would their response be fear and trembling and renewed interest in the God they are so convicted is real, or would they respond in fear and anger towards the messenger out of a wish to preserve their beliefs? What does that then say about their beliefs?

Just imagine the turmoil that would occur if a professor decided to speculate on something that was disputable. What about the implications of the theory of relativity for the second coming of Jesus Christ? What about the implications of quantum mechanics on our understanding of truth and knowledge? What about testing the Biblical claims for prayer and right living against the claims of other belief systems?

Seminary professors are accused of living in Ivory Towers, but as I see it our Christian congregations have put them there. Greg Boyd (who is controversial in his own right) was run off from his professorship because he dared to proposed a theory that, at least to him, made more sense out of scriptures than other widely known theories. I don't agree with Dr. Boyd on spritual warfare theodicy or open theism, but it does take seriously some passages of scripture that often aren't taken seriously enough. Another professor (who has requested to remain nameless) was fired from his professorship for writing a paper speculating that "abstacta" may be co-eternal with God. Essentially, what this means is that abstract concepts, like mathematical truths and logic are not "things" that need to be created, and therefore *could* be co-eternal with God. Again, I don't agree with this view, but it does take seriously the nature of certain truths. This paper had been published for over a year when he finally explained to one of his classes what the paper was really about. A student took issue with the concepts in the paper, and had the professor sacked for "not maintaining orthodoxy".

Incidences like these are not uncommon. So, instead of professors making their work accessible to all, in the hopes that their work might be an aid to the very church-goers who fund them, professors make their work as inaccessible as possible; they enter the ivory tower. They adopt jargon that takes much effort to decode. They use ambiguous language that makes the unsophisticated reader unaware of what they are really saying. They use an abundance of footnotes to intimidate others from criticizing their work. They make their argument philosophical, so that the implications to actual church practice (where the congregation resides) are hard to determine. They refuse to speak up in church to correct misunderstandings or misinterpretations of theology, or the Bible, or of history.

Professors often find themselves between the pressures to affirm the "orthodoxy" that congregations and students demand, and the call they feel God has given them to do profound and scholarly work to further the kingdom of God on earth.

I wonder what would happen if professors practiced church discipleship, teaching ways of interpreting the Bible, of thinking about God and science, and of the history of Christian thought. I wonder how most of the people in our churches would respond. How would you respond?

What would happen if we decided that loving God doesn't mean demanding the exact same formulations generation after generation, as if our ways of thinking about God are perfect and divine, but instead realize that loving God means going on the journey to grope after God, though He is not far from each of us? What would happen if the scholarship we, as Christians, fund actually makes its way into the life of our churches?

If it shouldn't impact us as the Church, then why on earth do we fund Christian scholarship?

Posted by Benjamin at 5:20 PM Labels: reflection, seminary

The concept of forgiveness intrigues me.

I was in a Bible study many years ago where we were talking about forgiveness. A single woman was talking about her yet-to-be-found future husband. She said that if her future husband ever cheated on her, she thought she could forgive him, but she didn't think she could ever trust him again. She said she would always have trouble trusting him, or wonder where he was when coming home late from work, or wonder who he was emailing. I don't remember what we said to her in the Bible study, but that story stuck in my head, because that is a story of forgiveness in which no one is actually forgiven. (It's actually more like the wrong kind of forgiveness.)

On the surface, forgiveness doesn't make a whole lot of sense. It seems to me that if you don't want a person to do something, like cheat on their husband, or steal, or kill, then you make the penalty so severe that it serves as sufficient deterrent. Plus, it has the added benefit of removing certain offending individuals from normal societal circulation so that their influence is minimized, if not eliminated all together as in the case of capital punishment.

Unforgiveness seems to make the most sense, because to forgive seems to mean that you open yourself up to being victimized again. Forgiveness seems like an invitation to a worrisome life, where you constantly have to cast a wary eye on the previous offenders, in fear of them offending again. Forgiveness seems to be an undesirable situation in which you have to adopt strange new actions that keep you from being hurt over and over and over by people who want to take advantage of your forgiveness. How does forgiveness ever really make sense?

As I've groped for a better understanding of the complex beast that is forgiveness, two Bible passages have shaped my thinking more than anything else, though the book "Faces of Forgiveness" comes close. One is Matthew 9:1-8, and the other is Matthew 18:21-35. (These passages are just 2 of many examples, but they tell the story in ways that really grip me.)

The Matthew 9 passage is a story about Jesus and the paralytic. When the paralytic's friends brought him to Jesus, Jesus told him that he was forgiven of his sins. After a bit of a scuffle with the teachers of the law, Jesus said:

Which is easier: to say, 'Your sins are forgiven,' or to say, 'Get up and walk'? But so that you may know that the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sins...." Then he said to the paralytic, "Get up, take your mat and go home." And the man got up and went home.

It seems to me that Jesus here is linking forgiveness to healing in a way that we frequently don't think about. At least in this passage, they are synonymous. Forgiveness and healing go together to the extent that "Your sins are forgiven" is the same as saying "Get up and walk".

Using this lens of forgiveness and healing, other passages start to make more sense to me. The parable of the prodigal son, for instance, isn't just about the depth of the love the father has for the wayward son, but it is also about the extent of healing extended to the prodigal. The prodigal wasn't accepted back into family life as the black sheep who would always be viewed with suspicion. Instead, he was restored, re-clothed, and loved in a way that doesn't quite make sense. It was the other son, the good son, who showed the kind of forgiveness that seems to make sense - the kind of forgiveness that merely tolerates the presence of those who are wayward, but never really trusts or accepts them back into right relationship. The "good" son rejects the healing embrace of forgiveness. The father knows better.

Paul exhorts us to remember to debt of love we owe to one another. Viewed through the lens of the healing embrace, if the prodigal son were to re-offend he would not be deterred by the violence of punishment, but rather by the crushing reality of life without the radical love of his father. The debt of love doesn't make make the prodigal fear the punishment heaped on him by others, but instead makes him fear thee punishment he heaps on himself through a life without the healing embrace. Perhaps that is also why Christians should visit the prisoners - to help them understand the healing embrace that they may have never had, and to welcome them into a community they never want to leave. Without such love and forgiveness, it's no wonder they re-offend.

Here's my point. If we are truly forgiven to the measure that we forgive, then perhaps some measure of our (my?) spiritual dryness is because we haven't learned how to give the healing embrace. Maybe sometimes the distance there seems to be between God and me (us?) isn't some inexplicable dark night of the soul, but rather a symptom of my own inability to forgive.

Perhaps the strangeness we feel at our family gatherings, or with our spouses, or in our Sunday School classes happens because we are constantly surrounded by people who don't know how to give the healing embrace, and are constantly wary of a relationship in which they might get hurt. Or, maybe it is us who can't give the embrace. Perhaps a portion of the animosity the secular world has for the church is because we have all failed in our ability to forgive in ways that mend, correct, and welcome.

I wonder how often what we call forgiveness is really no more than saying "that's okay". Instead, I wonder what would happen if we, instead of dismissing the moment of forgiveness, remembered Matthew 9 and extended forgiveness and healing as if they could never exist apart from one another.

Perhaps the true Kingdom of God happens when the true healing embrace of forgiveness is offered freely, even to those who want to see us dead. Maybe we, as Christians, need to be reminded a little more often of what a true healing embrace looks like.

But he was pierced for our transgressions, he was crushed for our iniquities; the punishment that brought us peace was upon him, and by his wounds we are healed.

Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.

Posted by Benjamin at 5:14 PM Labels: forgiveness, theology

I'm an introvert - a strong one at that. I need time alone and apart to recharge. I need time to process the things that have happened to me. I need time alone to sort through the emotions and situations and words and arrive at some semblance of an answer. I need time to reflect. I need time to figure out who I am in light of everything I have experienced, and everything I believe.

I'm an introvert - a strong one at that. I need time alone and apart to recharge. I need time to process the things that have happened to me. I need time alone to sort through the emotions and situations and words and arrive at some semblance of an answer. I need time to reflect. I need time to figure out who I am in light of everything I have experienced, and everything I believe.

If I recall, approximately 30% of the population in the

Since the majority of the American population are on the extrovert side of the fence, introverts tend to be misunderstood. I read a pretty good article a couple of months ago entitled "Top 5 Things Every Extrovert Should Know About Introverts". You should check it out - it's an easy read. To reiterate the article, introverts are not shy, arrogant, or socially inept, as they tend to be labeled. Instead, introverts are simply not group focused, intolerant of shallow conversation, and socially reserved.

In a society that values the quick satisfaction that can be given by a Google search, or by a cheap laugh from watching an episode of The Office, or by that energized feeling you get when you hang out with that ultra-extrovert who "brings the party", that misunderstanding cuts deep. Images of spontaneous interaction capture our minds and our hearts - whether it kissing a stranger in the street during a fit of joy, dancing with that strange girl in the club, or meeting the perfect guy in the baking goods aisle of the grocery store. These things capture us because, as extroverts see it, interaction is what runs the world. Things get done when people rub elbows, when they party together and get to know one another. People only get energized when they are around other people and can feel the closeness of human presence. The person who brings the party is the person who brings the life and energy to the world; the human dance is what gives motion to our being. In such a world, introvert is a dirty word.

And so, as I've done more often than I should, introverts make nice and act like extroverts in order to be accepted, even when they would rather find new friends at Borders Bookstore than at Williams Uptown Pub and Peanut Bar. Yet as I've considered the real hopes and fears and struggles of the people I've talked to, I've realized something important - everybody needs to know an introvert who acts like an introvert. And, everybody needs to know an extrovert who acts like an extrovert. With too many of the extroverts I know, communication can't get past the surface. Sure, there's a lot of talking going on, but not much actual communication that makes a difference. Sometimes lack of communication manifests itself as problems with family, sometimes as problems with getting into bad relationships, and sometimes as problems with thinking about God.

With too many of the extroverts I know, communication can't get past the surface. Sure, there's a lot of talking going on, but not much actual communication that makes a difference. Sometimes lack of communication manifests itself as problems with family, sometimes as problems with getting into bad relationships, and sometimes as problems with thinking about God.

Sometimes it takes an extrovert discussing their broken relationships with an introvert to figure out how to get past all the years of hurt and misunderstanding in order to actually communicate the depths of their feelings to someone else. Sometimes it takes having a deep conversation with someone familiar with the deep to help you figure out what you don't even know about yourself. Introverts help us to go deep. With too many introverts that I know, their thoughts are more important than the thing they are thinking about. I'm frequently guilty of this myself. Sure, there's a lot of thinking going on, but not much that makes a difference to what is being thought about. Sometimes this manifests itself as questionable statements like, "It's the thought that counts" or "Do what I say, not what I do." Sometimes, it manifests itself as being unapproachable, or unloving, or unrealistic about how the world actually works.

With too many introverts that I know, their thoughts are more important than the thing they are thinking about. I'm frequently guilty of this myself. Sure, there's a lot of thinking going on, but not much that makes a difference to what is being thought about. Sometimes this manifests itself as questionable statements like, "It's the thought that counts" or "Do what I say, not what I do." Sometimes, it manifests itself as being unapproachable, or unloving, or unrealistic about how the world actually works.

Sometimes it takes an introvert working alongside an extrovert to figure out how the thoughts and ideas and theories actually apply to reality. Sometimes it takes rubbing elbows with those who are outward focused to realize what a difference saying the little things actually makes. Sometimes it takes a quick conversation with someone who makes the world come alive to figure out what you don't realize about others. Extroverts help us meet with the real.

The reality is that we need one another. I can't help but wonder if the cosmic balance of human introverts to extroverts is on purpose. Maybe we need more doers in the world than thinkers. Maybe we need more people in the world to be the Mother Theresas, rubbing elbows, starting the party, and showing how to act in beautiful ways out of passion for action. At the end of the day, though, we need the Aquinas', too, thinking about the deep, churning up the dirt, and helping us to develop an internal dialog from which beauty may emerge.

But even in such a world as this, introvert is still a dirty word, because the deep is rarely pretty. Cover me, then, that I may have special honor.

...those parts of the body that seem to be weaker are indispensable, and the parts that we think are less honorable we treat with special honor. And the parts that are unpresentable are treated with special modesty...If one part suffers, every part suffers with it; if one part is honored, every part rejoices with it.

Posted by Benjamin at 4:40 PM Labels: introvert, personal, reflection, relationship

I went to a secular, state run University for my undergrad. I really didn't know what to expect, what with the drinking, drugs, and partying displayed by the media, but in college, I met many wonderful, Godly students. These friends were wonderful, and I've blogged about them before. They were sharp, they were committed to Christ, and constantly seemed to want to go deeper - to see how deep the spiritual well of Christianity goes. Well, as much as girl or boy crazy college students could. They challenged me and I challenged them. We weren't perfect by far, but when I think about what Christian community should look like, I often think of this group of college friends, struggling with God in their quest to find Him. At least, on the days I remember them favorably. I'm flighty that way.

A couple of years after college, when I entered Seminary, I expected to be greeted by students who reminded me of the Christian friends I had made at my secular university. I expected to find students who were sharp, well thought, interested in piercing the depths of what they didn't know, and excited by the new things they learned. I expected to find good students who read the assigned material and came prepared to discuss it, students who knew how to use the stacks and write good research papers, and who worked to integrate their reading and research into their Christian context. I, as a modestly read Engineer who had been away from college life for a few years, was prepared to be intimidated by my classmates.

Now, before I go any further, let's be clear: I'm more like the tortoise than the hare. I'm not quick and sharp and perspicuous, but I'm not dull, either. I am a hard worker, and continue to work things over until I get most of the wrinkles smoothed out. For some reason, I expected most of my classmates to be hard workers, too. (Or at least naturally gifted.)

I was disappointed. Just to give you an idea of the average student with which I interacted, here are some of the titles I thought about using but rejected because they were too harsh, even though they are intended to be a little tongue-in-cheek:

Matriculated Maladroit

Students are Stupid

In general, I found that seminary students tend to be on the bad end of the bell curve. I was disappointed in how easily confused most of my classmates were, how fearful they were of new ideas, and how poor their own sense of self was. I was also regularly disappointed as to how well these students did in class. Frequently, they neither read the material, nor turned their assignments in on time, nor knew how to use the library resources.

There were exceptions, of course. In my 7 years in seminary, during which time I should have seen 2 full groups of students graduate, I can only remember maybe 10 people who seemed to be able to intellectually function at a graduate level, and half of those were elitist. I would call those elitist "In the club" to Melissa, because evidently you had to know the secret handshake to qualify for meaningful interaction with them. But I digress.

A couple of years ago, I was listening to a speech by Stanley Hauerwas (a well-known professor at Duke who holds chairs in both theology and law) on the ethics of death and dying for Christians. Hauerwas casually peppered into his talk that seminary students these days tend to be people who have failed at their secular vocation, and think that God must be calling them into ministry. And, being the good Christian folk most professors are, these students tend to get softened requirements for making the grade.

I wish it weren't so, but Hauerwas' observation seems to be accurate. During classroom interaction, many student's couldn't reason through their own thoughts and would assert things that led to logical contradictions, conflicts of interest, or worse. Those who actually read the assigned material frequently couldn't find the real meaning of the reading and would be baffled about the themes we were discussing, or would find the bogeyman in everything and be afraid of the ideas being presented. Those who didn't read the material would surf the internet during class.

In any case, seminary taught me something important about grad school: dull people get master's degrees, too. This has led to a sad realization about the pastors our seminaries are churning out: they seem to be incapable of doing the intellectual work of the church.

In the early church, pastors were the ones who defended the faith against those who would undermine it with ideas that were logical contradictions, or conflicts of interest, or worse. People like Iraeneaus, Athanasius, the Cappodocians, or Augustine were defenders of the faith because being a pastor meant running a church and thinking about THE Church. But, I wonder, would our modern pastors be up to the task of refuting the heresy of the gnostics, or of Arius, or the the Pelagians? Are our modern pastors up to the task of redefining our ancient Christian ideas so that they can communicate the good news of Christ? Instead, will our pastors sit confused and baffled while heresy grows, or perhaps be fearful reactionaries to any ideas that are new?

I'm partially comforted by the fact that Jesus' disciples seemed to be a bunch of dimwits, but turned out to be powerful agents of Christ in the world. That comfort is tempered, however, by the general decline of the American church.

What do you think? Are there ways in which you feel church leadership has been a disappointment?

Posted by Benjamin at 12:41 PM Labels: reflection, seminary

Dovetailing with the lesson that hermeneutics matter, Seminary also taught me that languages are important.

Even before I went to Seminary, I knew that languages were a big deal. The Christian tradition in which I was raised holds that scripture is inerrant in it's original form, which includes the original language in which it was communicated. For most of scripture, these languages are Greek and Hebrew.

The more I learn about other languages, the more I appreciate how distinctive they are from each other. I spent some time in Merida, Mexico when I was in college. I had learned the word "simpatico" in my spanish classes, and it meant something like "nice", or perhaps "friendly". When I got to talking with my Mexican hosts, I realized that there is no English word that captures the meaning behind "simpatico". Simpatico, properly translated into English, would mean something more like "friendship between people that is so profound that these people fit together as if they were designed to be in relationship with each other". Best friends are simpatico. But, as I was taught by my Mexican friends, simply calling a person "simpatico" because they are friendly or nice is a misuse of the term. Simpatico is much more intimate than friendliness, and it could be seen as offensive if you call someone simpatico when you only casually know them.

Another example is with the English word "predicament". I saw a video interview with Paul Tillich (a prominent 20th century German theologian) once, and he mentioned that there is no equivalent word for "predicament" in the German language. Predicament, he said, was a wonderful English word that described so much about humans and their relationships. Using a concept like "predicament" in German, he continued, required much unpacking.

Even though we have excellent English translations of the Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic, seminary gave me a better appreciation of what is lost when translators try to cram complex foreign words into simple English equivalents (or vice versa). On top of that, word plays and poetry lose much of their power when translated.

For instance, one of the first passages I translated from Greek was John 3:16. In English, it goes something like "God so loved the world that he gave his only son, that whoever believes in him should not perish, but have eternal life." Now, what does it mean to say that "God so loved the world"? Most people who speak english thinks it means "God loved the world sooo much that he sent his only son....". That's what I thought it meant before I was taught Greek. But it's wrong. In fact, the word "So" is the greek word "houtos", which means "thusly; in this manner". The translation then becomes, "God THUSLY loved the world..." -or- "God IN THIS MANNER loved the world..." At least in this case, the Bible doesn't teach that God loves us sooo much, as if the gospel message is similar to Romeo and Juliette. Instead, it teaches us HOW God loved us, and how we should therefore love others.

Makes a difference, doesn't it?

Wordplays make a difference in Genesis 1:1. In the Hebrew, this verse is highly unusual in its structure, and there also seems to be a word play. The word for "In the beginning" seems to be carefully chosen (and slightly mispelled) to simultaneously mean "begining" (reshit), and "create" (bara). Many people think that Genesis 1:1 is meant to be historical fact about the ordering of creation. The fact that the first verse (and many others) in Genesis is a tricky, artfully crafted sentence that has defied precise translation lets me know I shouldn't be so sure this was meant to be a story of historical fact.

Languages, as viewed from the standpoint of translations, are important.

As an American, I love the English language. Not only is it flexible, being both precise and beautiful, but it is also spoken almost everywhere. But when I hear English-speakers insult other languages, or declare that everyone in their community needs to speak English, I become concerned. The way I see it, the last time too many people got together and all spoke the same language, they tried to glorify themselves by building the biggest structure they could. For some reason the Bible doesn't make clear, God found this group of people speaking the same language lacking, and chose to confuse their language. Whether or not this story is symbolic, it does tell me something important - languages are a tool used by God.

What if, I wonder, that Latino who lives down the street and speaks bad English actually teaches me about simpatico in a way that draws me into a new way of thinking of Christian community? What if, as that Bavarian with whom I work describes his understanding of predicament, I realize how profoundly different from God I really am? Speaking English makes me feel proud and accomplished, as if I can make a name for myself that everyone can read and understand. Realizing the nuance of language tempers my pride.

Languages, as it comes to understanding our place in creation, are important.

I find it immensely wonderful that Christ sent me a Spirit that intercedes for me in ways that are beyond words. The language of my prayers are insufficient to capture the core of what I am trying to say to God. As much as I might be proud of my education and command of the English language, it is still a flimsy tool that I use to describe reality. The coming of the Spirit takes my attempts at articulation and translates them into a language beyond the inadequacies of creaturely language. The Spirit says for me what I am incapable of saying myself. The language it speaks get to a deeper reality than words ever can. It is amazing and humbling that God finds my finite being - my needs and my praises - to be beyond the very means I use to describe it.

Yet the Bible also teaches that the Spirit plumbs the depths of God, and reveals those depths to me. If my finite nature is beyond words, how much more complicated is the language the Spirit uses to reveal God to me? The language I am being taught, day after day, as I strain towards the mark, is the language of the divine.

Language, as it comes to understanding the infinite God, is important.

My prayer is that the words of our spoken language are continually colored by the unspeakable language of the Spirit. By that language which is beyond words may we find what is truly important.

Posted by Benjamin at 10:12 AM Labels: reflection, seminary

Probably the single most important lesson I learned in Seminary was the role of hermeneutics.

I thought I knew something about interpretation and cultural embeddedness when I entered school. I was wrong. The depth of the chasm between our modern day way of living, thinking, and writing and the Biblical contexts is huge, and has changed much of how I conceive of God, Jesus, Christianity, the Church, and scripture.

In my Christian upbringing, the Bible was considered something not tainted by cultural or historical forces, that stood on its own apart from any serious interpretation issues. In short, the Bible was this thing that was clear and plain for anyone to read. Disagreement about interpretation of the scriptures meant that you were wrong, and needed a little more submission to the "clear and plain" commands of God.

As I've rubbed elbows with Africans, African Americans, Hispanics, and Chinese Christians, I've come to realize how heavily interpretation depends on the place we come from. For me, it comes from a white, middle-class background in which education is a given, democracy is given, and individualism is highly valued; my hermeneutic is borne out of the legacy of freedom. For the older African Americans I worship with, their framework of understanding scripture is borne out of the legacy of oppression. Based on these legacies, the differences in understanding what scripture is saying can be stark and harsh.

I've come to realize that this cultural and temporal experiment in which God has placed all of us is valuable in understanding the many aspects of God, but horrible for understanding this a-cultural scripture I was taught about.

The lessons of hermeneutics, though, tells me that the authors of scripture were part of the same grand experiment that we are. I can't just jettision middle-class america and think I can interpret scripture as if it is "plain and clear". Instead, I must slowly and painstakingly transform my understanding to be a first-century Jew, the remnant of the Chosen People of God, oppressed by Rome, and witness to this Messiah who ripped to shreds every notion of what I thought a messiah should be. I must transform my understanding to be like the ancient Hebrew who thought that gods were things particular to a geography, or to be like the Israelite who is part of the kingdom of David. The distance between me and them gets greater the more I work to understand the Biblical authors, and the more disturbing and radical scripture becomes as I understand what those Biblical authors may have really been talking about.

Clear and plain, I have learned, is a myth prescribed by those who don't understand the true gulf between the modern "us" and the ancient "them".

One of the places I have come to appreciate the New Testament better is through the image of Kingdom. The overwhelming majority of scripture speaks of Jesus coming to set up the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth. Not to save me, as if His only goal was to take me from hell to heaven. Instead, His goal was broader than my individualistic culture - it was a kingdom, a people, an extended community - the problem Jesus was trying to solve wasn't answered by me getting "saved", it was answered through a kingdom!

What on earth can this possibly mean for the way I (we?) do Christianity?

Posted by Benjamin at 1:55 PM Labels: reflection, seminary, theology

This June, after seven years in Seminary, I finally graduated with my M.Div. Now, before you snicker at how long it took me to graduate with a degree that can be done in 3 years, is billed as a 4 year master's, but usually takes students 5 years, keep in mind that I also worked 40+ hours a week during my seminary tenure. Seminary was my part-time love.

Many seminary grads I have talked with over the years didn't feel like they learned much in seminary, but I feel like I learned a lot. Over the next few weeks I'll be talking about some of the lessons that I learned in Seminary. Some are great academic lessons, and some are more stark realizations about the nature of things. Both were valuable.

As I mentioned in my last post, the overwhelming majority of my life has been spent in school. Even though I was a part-time student, I spent the majority of my "free time" these last 7 years reading, researching, and writing. These, as is common knowledge, are very manly activities.

Let's face it, I'm not the manliest man there's ever been. At least, not in the whole "I spend all Sunday afternoon watching sports" or "I rode my Harley from here to Mexico City without taking a shower or using the bathroom" sort of way. But, I still enjoy manly fare. Occasionally smoke a cigar? Check. Work on my own car? Check. Chop a whole bunch of wood because it's there? Check. Shoot firearms because of the loud bang? Check. Mow the yard in a wifebeater? Check, sorta.

Reading, writing, and research doesn't really fit on that list. Does it make you feel intelligent, accomplished, and superior? Check. Does it make you feel like a hunter/gatherer with cunning and skillz? UnCheck. And you know, I think I could be okay with that - this emasculating they call "higher education" - if only the whole thing would end in a really big bang. I don't know - with a ropes course followed by explosions or celebratory gunfire or something, followed by roasting a pig over a fire we made with our bare hands. Just something.

But instead, how does it all end? They make you put on a hat shaped like a pizza box, a silky see-through gown, and then they make you kneel on stage while they put a shawl (a.k.a., a "hood") on you. Oh, and if you did really good at reading, writing, and research, you get special "accessories", like a golden ribbon to tie around your neck. I thought it would be cool to do some face paint or something to show how pumped I was about this whole thing, but I was told in no uncertain terms that face painting was not allowed. Though, I could swear some of the women painted their faces...

Now, don't get me wrong, I really appreciate my seminary journey more than you can know. But at the end of the day, I wonder if some of the problems the church has communicating with 20 and 30-something men has something to do with the way in which our church leaders are taught. I have a hard time understanding how reading Iraneaus, Tertullian, Augustine, Anselm, Descartes, and Tillich helps anyone penetrate the modern masculine psyche.

But I did get my party. Many wonderful old friends and family came to celebrate with me. We ate meat - lots of meat. With barbecue sauce and baked beans. Which led to another manly activity that shall not be spoken of out of politeness.

I love Ecclesiastes 7, though Ecclesiastes is often grossly misunderstood. This seminary chapter of my life closes, and I can honestly say, "The end of a matter is better than its beginning, and patience better than pride...wisdom, like an inheritance, is a good thing and befits those who see the sun."

Here's to leaving the reading chair empty a little more often, and going out to see the sun.

Posted by Benjamin at 2:20 PM Labels: reflection, school

In the book Summer of the Monkeys, a country boy in the late 1800s or early 1900s, named (if I remember correctly) Jay Berry Lee, spends his summer on a quest to earn enough money to buy himself a pony and a gun. Along the way, he finds out that a large group of circus monkeys escapes near the woods where he lives, and that there is a large reward for the person who finds them - a large enough reward to buy his horse and gun outright.

In the book Summer of the Monkeys, a country boy in the late 1800s or early 1900s, named (if I remember correctly) Jay Berry Lee, spends his summer on a quest to earn enough money to buy himself a pony and a gun. Along the way, he finds out that a large group of circus monkeys escapes near the woods where he lives, and that there is a large reward for the person who finds them - a large enough reward to buy his horse and gun outright.

Capturing the monkeys proves to be a challenge. They're a wily folk, those monkeys. They trick Jay many times, they get him drunk (I bet that's not in the Disney version!), they get him in trouble, and generally prove hard to control. But, in the end, they're also fragile, and when a giant rainstorm blows through and the weather turns cold, they willingly surrender themselves to Jay to be taken care of, and Jay gets his reward when he gives the monkeys back to the circus.

'Course, being a children's book, Jay learns some lessons along the way about the evils of liquor, about compassion, about using his time wisely, and about how to make hard decisions. In the end, the real reward for Jay isn't the money, but is the summer he spent trying to wrangle a group of circus monkeys. (He got another reward too, but I'll let you read the book to figure that one out.)

I think about this book sometimes when I think of carefree summer days, spending time on whatever strikes your fancy, or when I think about what it must feel like to not worry about what comes next.

My circus monkeys just showed up out of nowhere. They're a wily bunch, hard to control and conniving, but they're also fragile and lovable. Ultimately, the real reward isn't the stuff I got this summer (and I got some cool stuff), but is the summer I spent trying to wrangle a couple of circus monkeys.

I also got to spend some much needed time off, thinking about things outside of my property line only when I needed to, which ended up not being very often. For an introvert like me, taking time to recharge is the way I learn about compassion, and how to make the hard decisions, and, uh ... the evils of liquor. Hmm, I guess the analogy breaks down at some point, doesn't it?

Oh, well. It was fun while it lasted.

Posted by Benjamin at 4:50 PM Labels: kids, reflection, Summer

What can I say? I'm totally addicted to Lost. My VCR is set up to record it every week, but instead of waiting for it to finish recording so I can fast-forward through the commercials, I watch the show while it is being recorded. I just can't stand for my Lost fix to happen even one hour later.

The series has had it's ups and downs, and to be honest, the current season hasn't been quite up to par. But the last three episodes have been fantastic. Last week's episode had me thinking about it for days. Truth be told, I'm still thinking about it. I have tons of questions, like

- Is Ben crazy? (Ben is a character in the show. For the record, I AM

crazy. Hehehehehehe.)

- Is Locke crazy? (Or dead?)

- What was that grey substance on the ground around Jacob's cabin?

- Who are the hostiles and where did they come from?

- Why doesn't Richard Alpert appear to age?

- Is Juliette really defecting to the beach dwellers, or is she a triple agent?

- Is Jack getting played by Juliette, or is he in on the whole thing, too?

The only real fatal flaw in Lost is that it is highly serialized. You can't just jump into Lost and get into the swing of it. Oh, no. That would not only be frustrating, but would also do enough violence to the story that has come before that it would be almost criminal. You can't just jump into the middle of a novel or a movie, now can you? 'Course not. And Lost is no different.

But, like I was saying, this is the fatal flaw of the series. You won't have a clue what is going on until you've seen what came before, and to see what came before, you have to go all the way back to Season 1 of the series. I think this is why I can't find many people who watch the show, because if you tried to start with Season 2, you would be totally lost. (No pun intended.) I think that's why I can't find any kindred spirits that are into Lost. I mean, someone other than me has to be watching the show, right?

So, I'm thinking about renting the series on DVD and have some Lost parties at my house in preparation for Season 4, which will start in January of next year. We'll all sit around in my basement, get a fire going in the fireplace, eat some popcorn and sugarbabies, and watch 2 episodes of Lost a week until Season 4 starts. Or something like that.

Who's with me?

Posted by Benjamin at 3:19 PM Labels: Lost, Television

Wow - it's hard to believe that Easter was over two weeks ago. Where does the time go?

The Christian holidays surrounding Easter are very underrated in my evangelical tradition. There is Maunday Thursday, Good Friday, and Easter, followed by Ascension 6 weeks after Easter, and Pentecost 50 days after Easter. It has always seemed bizarre to me that these days are not more prominent in church life. Is it perhaps because we don't give candy to our kids (as in Easter), or give each other presents (as in Christmas) that the command given to the disciples on Maunday Thursday, or the atonement on Good Friday, or the Ascension of Christ into heaven, or the coming of the Spirit on the apostles at Pentecost fades away as unimportant? Maybe adults are afraid to take seriously these more somber holidays because that would mean that Christianity itself would have to be taken more seriously?

I've been thinking this year specifically about Good Friday. Good Friday is the day when Jesus was crucified. Biblically, there were several things leading up to this day, but one thing really sticks out to me: Good Friday happened during the Passover festival.

It seems to me that most Christians believe that our sins were forgiven when Jesus died on the cross - that his death was an atonement for our sins. I don't disagree with this. But, the Jews already had a festival for atonement called Yom Kippur (which means "Day of Atonement" in Hebrew). Biblically, this is considered the day of repentance, where people are reconciled to each other and to God. This Jewish holiday is fascinating to study, but one of the most interesting parts is when the High Priest lays his hands on a goat and confesses the entire sins of Israel. While he does this, the people in the crowd were supposed to confess their sins, too. Then, the goat is sent out into the wilderness never to be seen again. The symbol here is that the sins of Israel - including the sins of individuals - were put onto an innocent animal, which was then separated from the people. Their sins were literally carried away and lost in the vastness of the wilderness.

It seems to me that the symbolism of Yom Kippur might fit the atonement that happened at the crucifixion. Yet, Jesus chose to be crucified on the holiday of Passover. Why Passover?

Passover, if you remember the story in Exodus, was when the Israelites smeared the blood of a lamb on their door frame so that the angel of death would not kill their firstborn. This event marked the last in a line of plagues brought against Egypt because they held God's people captive. When the Pharaoh woke up and his firstborn son was dead, he finally relented and let the people of Israel go free. Passover was a time of liberation from bondage.

Why Passover? Maybe Jesus was making a point by going into Jerusalem during the Passover feast. Maybe Jesus was choosing to symbolize his death as liberation from bondage - as freedom from slavery and oppression. Maybe he is choosing to say that his body and blood - given to the disciples on Thursday - deflect the wrath of the angel of death. Maybe he is choosing to tell the story that the awful events of Good Friday were the end of the plagues, and the beginning of freedom. Maybe Jesus chose passover because he is choosing a story that signifies the beginning of life.

Certainly, themes of atonement have a place in Jesus' crucifixion. As I reflect on Easter week, however, I find that the story of freedom makes sense, too. Not just liberation from sin and death, but freedom to LIVE.

"I have come that they might have life, and have it to the full." John 10:10b

I like to think about history. Some history is easy, such as the history of my friends - how they got from point A to point B in their lives. Some history is hard, such as how the entire country of Germany could become so arrogant that they tried to take over the world in World War II.

I suppose I'm not too interested in dates and places - I can't really remember many dates at all. I'm more interested in the event and how the event affected what came after. How did the events in the lives of my friends get them to where they are today? How did the events in the history of Germany lead them to warmongering and genocide? I'm interested in the trajectory of things.

And so I spend time thinking about the future, how the things that happened yesterday or today will play out in the future. I think about my own trajectory, the trajectory of my kids, of my friends, of my church, of the Church. I think a lot about the future. Not because I'm worried about it, but because I want my vision of the future to effect how I live life today.

When I think about the future, the ULTIMATE future, I am convinced that I will be consummated with Christ. But what does that mean for how I act today?

To answer this, I think a little more about history. The Biblical authors seemed to think that this consummation with Christ would happen within their lifetime. It didn't. Neither did it happen within the lifetime of the next generation of Christians, nor the next, nor the next. The ultimate future that we, as Christians, expect to come hasn't come for 2,000 years. And it might not come for 2,000 more.

Yet the Biblical authors were filled with a certain sense of urgency concerning Christ's return. They didn't think that because Christ was coming soon that they weren't going to get much accomplished. Instead, they devoted their lives to the fellowship, to preaching and teaching the good news of Christ. They built communities of faith who took care of each other - they strained towards the goal that Christ taught while on earth. Their belief in the coming of Christ spurred them to action.

So, when I hear Christians say things like, "I just hope Christ comes back before that," I'm chilled to the core. James Watt, the secretary of the interior during Ronald Regan's presidency is well known for saying, "We don't have to protect the environment, the Second Coming is at hand." In the conversations I've had, many Christians seem to believe something similar to Mr Watt. Or, when I hear preachers saying that Sodom and Gomorrah need an apology if Hollywood or LasVegas or *name any city here* isn't judged harshly by God, I become severely troubled in my spirit.

Since when is the immanent coming of Christ an excuse for judgmental or lackadaisical attitudes? It seems to me that the Biblical example is that the immanent coming of Christ should motivate us to action - to build strong communities of faith, to start missions to those pagan cities who need Christ more than they need God's judgment. It also seems to me that the perspective God has given us as 21st century Christians is that the ultimate consummation with Christ might also be far-off, so our Christian stewardship on every level should show to those who come behind us how faithful we really were. Instead, I see many Christians behaving as if the work of Christ will have to wait until Christ returns.

Here's my point - our ultimate consummation with Christ isn't just about some future event. Consummation with Christ happens now - today - as I let myself become consumed with the very thoughts and actions of Christ to the point where I want to act out his mission in the world. Consummation with Christ is a future thought that affects me today as I am led by the same Spirit that led Christ to rebuke the false religious teachings of the day, to offer forgiveness and healing to the tax collector, the prostitute, and the blind.

Being consumed with Christ means I have an urgency to do his work - to proclaim the good news. But knowing that his return could be another 10,000 years also sheds new light on Jesus' phrase "The kingdom of God is in your midst" (Luke 17:21), indeed, all the other passages about the Kingdom of God indicate something similar. The Kingdom of God isn't just some far-off place that we'll get to in the future - a significant part of the Kingdom of God is now, in those who gather together with the same Spirit as the Apostles, to be consumed with Christ.

This is my favorite future thought - that the coming of Christ (whenever it may be) consumes me so that I live today as if it already occurred. Not that I don't struggle with things, but that my trajectory is determined by events that haven't yet occurred. This lends new meaning to the saying, "Forgetting what is behind, and straining toward what is ahead, I press on towards the goal to win the prize for which God has called me heavenward in Christ Jesus." (Philippians 3:13)

It's time I tried my hand at greasing the skids. I'm tired of having old, rusty skids that don't run smoothly. So, you know what I'm going to do?

No, random blog reader, not that. Frankly, I'm a little disgusted and disturbed that you would bring that up.

What do you mean you know I tried it? Who have you been talking to? Have you been going through my trash? Whatever you found, it wasn't mine. I get all kinds of mail from the previous resident of my house. I would try to forward the new mail to him, but he's dead. It's not a crime to open a dead man's mail, is it?

Oh, it is. Well, it wasn't me that opened it, anyway. I was going to write "recipient deceased" on the mail and send it back, but my kids got into it before I could do that. And, being illiterate children, they opened it. I don't think you can prosecute a 2 year old for opening a dead man's mail, can you? Yeah, I didn't think so.

Back to who you've been talking to - very clever trying to change the subject to me opening mail illegally, you almost had me. But I've got a mind like a steel trap. Who have you been talking to again? Oh, her. Yeah, well, you see I only tried it that once and I didn't enjoy it at all. And, uh, it was an accident, really. I was just going along, trying to figure out if you could play tennis with a racquetball, when...

What's that you say? You talked to her in a bar? Well, obviously she was drunk. You can't trust the drunken ramblings of a drunk woman, now can you? Surely not. Especially when I have it on good authority that she is a conniving drunk. Plus, I hear she likes the hard stuff, which, you know, gets you drunk a lot faster. At least, that is what I was told in DARE in junior high. I've personally never even been tipsy - it's not the ninja way.

I don't care if she was the designated driver - even the smell of liquor is enough for some. Oh, you were in a piano bar. Well, that makes it even worse, because music is intoxicating on its own. Piano rock is the new crack cocaine. I think I read that in Rolling Stones magazine. Don't bother looking that up, my mind is like a steel trap. So, clearly, you can't trust some fluzy you met in a piano bar who is smoking crack, now can you?

What's that you say? She's your sister? *Wheeze* Uh, who is this girl again? Yeah, now that you mention it, I'm not sure I know who that is. I meet so many people, you know, being as extroverted as I am. I just don't remember if I ever knew her or not, you know, it's been so long...

Well, sure, I said my mind is like a steel trap, but that's just a saying, it doesn't mean anything. Sorta like "a stitch in time saves nine" or "talk is cheap" or "blow chunks" or "greasing the skids". It doesn't really mean anything, its just something you say to keep the conversation going.

Now, where was I again?

Posted by Benjamin at 1:19 PM

When I woke again, it was light outside, and the storm had passed. The bed was empty, save me, so I got up to eat breakfast and look for him. I made my way into the kitchen and made some toast, then wondered out onto the porch to sit and enjoy the crisp air and beautiful scenery brought on by the morning. The air was damp, from the rains the night before, and cool. The ground was damp, too, and the rocks glistened with a slippery grin. The bark on the trees was dark, making the contrast between the brown of the trunk and the green of the canopy even more picturesque. A slight fog seemed to rise over the forest in the opposing side of the valley, and it seemed to tumble lazily into the valley below as if it was on a stroll to greet me good morning before the sun stepped out from behind the mountain and burned it away.

I had sat on the porch for maybe five minutes when I heard a familiar voice urgently calling my name. I casually walked down the narrow road, following the sound of his voice, and found him high up on the embankment. He was obviously excited about something, and as soon as he caught sight of me, he started saying something rather quickly that I couldn’t quite make out. Staying on the road below him, I walked over to where he stood so that we could talk, and as I did so the steep incline of the embankment and the narrowness of the road forced him to step closer to the edge to maintain eye contact with me. When I finally stopped walking and could concentrate on listening I could tell, despite his rushed speech, that he was talking about the waterfall, that the storm the night before had caused it to swell, and he wanted to know if I wanted to hike back with him to see it. Waiting for my reply, he stepped a little closer to the edge. I paused for a moment, trying to decide if I should go back and change clothes first, and in that brief second the ledge up on the embankment collapsed. My companion toppled, almost twenty feet straight down, and landed on his back in the rocks with an audible thud.

I am certain that my heart skipped a beat in the instant panic that seized me, and I rushed over to him as fast as I could. He was lying precariously off of the edge of the rocky cliff, with his right arm and leg dangling, and his left leg millimeters from slipping off. He was trying to pull himself back onto the road when I reached him, but something was wrong. He wasn’t moving right, and he couldn’t make his arms work to pull himself back onto the cliff. I grabbed his left arm with one hand and put the other under his shoulders to try to lift him back onto the road, but I was weak with fright, and his body was limp, like dead weight. I simply couldn’t do it. I decided instead to hold him there for a moment and stabilize him until I could run back into the cabin and call for help on the radio. I stopped and looked at him, and gazed into those eyes that were this time a flinty grey. He was bleeding from his ears and nose, and his breathing was hoarse and ragged. He blinked his eyes once or twice slowly, and each time he opened them, they were more glazed and flinty. I started to cry. “I’m going to the radio to call for help,” I told him. “I’ll be back as soon as I know someone is coming.” I tried to get up to leave, but his left arm held me tight, and I couldn’t pull myself free. I struggled and pulled and cried and begged him to let me go for help, but he would neither let go, nor could I pull him off of the ledge. I sat back down, drained, and held him in my arms. His breathing stopped and started, and then he caught my eye and attempted a weak smile. “I wanted you to have this,” he whispered, and he pushed his clenched right hand into my chest. I let go of his left arm and held his hand there. “I love you,” I murmured. He gave me a weak smile that I could barely make out through my tear filled eyes. He exhaled, and his eyes glazed over and lost their focus.

His body went limp and he started to slip off of the edge of the cliff. I moved to catch him, and as I did so I let go of his right hand that I had clutched to my chest. His arm swung downward, off the edge of the cliff, and his grip released, and all I saw was a brief glimpse of gold and a glitter before the contents of his hand spilled into the valley below. Somehow, I pulled most of his body back onto the ledge, my tears raining drops of sorrow onto his body all the while. I went to the radio and called for help, and after what seemed like an eternity a helicopter and a small truck arrived on the scene. They asked me questions and shined lights in my eyes and took my pulse and blood pressure. I was cold, shivering as a matter of fact, and they gave me a blanket and put me on the helicopter. As we were leaving I caught sight of them loading a stretcher blanketed with a shroud onto the truck.

I cried for days after that. Nothing seemed to fill my loneliness or ease my grief. I would sit in the rain and cry, and for those few minutes it seemed as if the whole world was mourning with me. I wondered in and out of our café, almost feeling like I was looking for something, but I could never bring myself to sit or to buy anything. Everything seemed so bland and grey and.....pointless.

I called and talked to the people who came up the mountain to help me, looking for some answers. They said that the rain from the night before must have loosened the rocks on the embankment. That is probably why it collapsed. Also, the doctors told me that he had sustained severe blunt trauma to the head, and had shattered several vertebra, so he was more than likely paralyzed for the last few minutes of his life. The trauma to his head was so severe, they said, that there was a large amount of bleeding into the brain, and that even if they could have gotten him to a hospital in five minutes, they still couldn’t have saved him. But even the answers to my questions didn’t quiet my grief, or help bridge the giant chasm ripped in my heart. Nothing but time did that.

It took a lot of time. Time to learn how to get out of bed every morning. Time to learn how to interact with people in public. Time to stand on my own without waves of grief striking me down. Time to learn how to be happy just with who I am. It took time to learn how to do all of this with a gorge through the softest part of me. But time wears down the sharp peaks and smoothes out the jagged edges until, eventually, the land is flat again. Different, but flat. And as I learned to be a whole person again, I realized that I kept a part of him with me. The parts that were subtle and rule bending and spontaneous and adventurous are part of me now; his enduring presents to me. I get to wear them, and while I may not be able to wear them as well as he did, they are mine, and they are all that is left of what he had.

Sometimes, now and again, I think that it is about time to start over. To begin again. To share some of these new things that I wear with someone else, in the same selfless way that he shared so many things with me. But I’m scared. My pain hasn’t killed me, but I’m not sure that it has made me stronger, either. I’m different than I was before. I enjoy my solitude, because I know that no one can hurt me that way. But what kind of life is that? What kind of life is it to sit here on a park bench with the pigeons on a gorgeous Sunday afternoon? One that I’m content to lead alone, I suppose. Maybe it is time to start over, to learn how to become intertwined again. Things will be different this time, as each time always has been, but the journey is part of the gift. Maybe it’s time to sit down in a café again and discuss coffee beans with someone, and find out just how far this human heart can go.

Posted by Benjamin at 12:43 PM Labels: intertwined, writing

I'm not sure much changed between us after that first kiss. I already spent every moment that I possibly could with him, and the topics we discussed had already spanned the spectrum: from sex to God to pharmaceuticals to international politics and how they inflated the price of coffee beans for the common laborer. Only now, however, I had access to his lips almost any time I wanted, and I partook of them liberally. Many an evening he let me venture close enough to those lips to touch them to mine, and more than a couple of times we fogged the windows of his car with our passion. Somewhere in this time something inside of me changed, and I no longer wanted the seclusion of my own life, but instead what I wanted was to pull close to him and lay in the security of his arms forever.