For some unknown reason, my church lets me teach the youth on Sunday morning about twice a month. This is a little bit of a surprise for me, because, if you've ever read my blog, I border on being really bizarre, and a bit off the beaten path as far as my thoughts about church, the Bible, and spirituality. Still, someone has seen fit to let me teach, and the youth and I generally have a good time.

For some unknown reason, my church lets me teach the youth on Sunday morning about twice a month. This is a little bit of a surprise for me, because, if you've ever read my blog, I border on being really bizarre, and a bit off the beaten path as far as my thoughts about church, the Bible, and spirituality. Still, someone has seen fit to let me teach, and the youth and I generally have a good time.

We happen to be going through Genesis right now, and not too long ago, when we read through chapter 3, which is the Fall, someone asked how mankind can be condemned for sinning if God a.) knew that mankind would sin, b.) created them with the particular nature that would be succeptible to a talking snake, and c.) set them loose, knowing full well what would happen, but d.) chose to do nothing about it. This kid's argument, such as it was, is that there really isn't such a thing as free will, but rather God ordains the ways things are, and there isn't much that can be done about it. If there was something we could do about it, then God's view of the future would be wrong, and he wouldn't be God.

Based on that, here's the question he asked: How can we be said to have free will?

Before I go too much further, let me just make the disclaimer that most of the stuff I'll say is off-the-shelf theology. I didn't come up with this on my own. But, as I've been thinking about the question of free will (especially as it relates to evil and the problem of good), I've come to a better appreciation of this stuff.

How would you answer this youth's question?

The answer I was always taught is that God gave us the ability to make decisions because he didn't want robots. He wanted people who could choose to worship him. It's just a bummer people chose something else. It's not God's fault - he created us perfect. The problem is that humans took what was perfect and perverted it.

But isn't a being who will pervert what is perfect not, in fact, perfect? (Unless, of course, it is perfect in that it is a perfect perverter. Then, you have to wonder what kind of God would create a perfect perverter.) The fact of the matter is that looking at humans as having free will is problematic in almost every way. Note that this will be a gross oversimplification, but either man has free will (the Arminian position), in which case God just sits back and allows things outside His will to happen yet remains blameless, or God is completely sovereign (the Calvinist position), in which case everything that happens is part of God's plan and man should not be held responsible. Isn't there a way to think about free will, or the lack thereof, other than these two options?

Why do we even think of things in terms of free will? I mean, I can't levitate, or walk on the ceiling, or drive my car over the ocean. I can't choose to cure cancer or fly like Superman. Aristotle (I think it was Aristotle) said, "A man is free to throw a stone, but not to recall it." How true that is. Even if I will the stone to stop flying through the air, it won't stop. Even if I will to fly like Superman or drive my car over the ocean, or cure cancer, my will is unable to make that happen. My will is not free to do these things.

So, why do we even think we have free will? I think, personally, we think this because we don't know any better. If push comes to shove, we could come up with a hundred times more things we CAN'T do than things we CAN do. Yet, because we get so used to operating in the arena of stuff we CAN do, we think we have free will because we forget about the stuff we CAN'T do.

So, because there are so many things I can think of that I can't will to do, I don't think we have free will. Our will is definately not free to do whatever we want, instead we are constrained to a very small portion of what is possible. On top of all this, the Bible doesn't even talk about people having free will. It's simply not a topic the Bible addresses. Free will, at least the way most people think about it, is a myth. Free will doesn't exist.

What the Bible does talk about are decisions. One decision can open up the option for more decisions. For instance, making straight A's in school opens up a ton of options for the future. On the other hand, taking drugs (or getting a felony) closes options for the future. The further you travel down either of these paths, the more options the good student has, and the fewer options the addict has. What the Bible teaches is that good decisions breed options for a better future.

The story of the Bible is that people couldn't learn this lesson. So, God called Abraham out of paganism, and created a chosen people and nation to help the world understand how good decisions (good stewardship of resources, the land, taking care of each other, and worshipping God) leads to a better future for everyone. But even the Jews couldn't get this message straight. So, God sent Jesus to show us an example of exactly how to live a life full of good decisions. But humanity couldn't tolerate such a person, so we killed him.

Nevertheless, Christ came to show us how to be free. Ever since Adam and Eve, we've been so mired in selfishness and greed, envy and malice, violence and indifference that we can't make good enough decisions on our own to secure a good future. We are a slave to sin, a slave to the limited options that are the result of our bad decisions. We are the addict who's options are constrained by his choices. But Christ came to break the cycle. He came to show us how to make good decisions, and to choose the things that give us options for the future. He came to show us how to be the good student, and open up a future full of options and hope. Christ came to show us how to gain freedom from what otherwise binds us. Christ came to show us how to be free.

Nevertheless, Christ came to show us how to be free. Ever since Adam and Eve, we've been so mired in selfishness and greed, envy and malice, violence and indifference that we can't make good enough decisions on our own to secure a good future. We are a slave to sin, a slave to the limited options that are the result of our bad decisions. We are the addict who's options are constrained by his choices. But Christ came to break the cycle. He came to show us how to make good decisions, and to choose the things that give us options for the future. He came to show us how to be the good student, and open up a future full of options and hope. Christ came to show us how to gain freedom from what otherwise binds us. Christ came to show us how to be free.

This is why I have free will. I have free will because Christ is showing me every day how to make good decisions that open up my future to have better options. My will is continually becoming free to chose more and more options because the decisions I make are guided by an understanding of what God has revealed in Christ. It's not that I have "free will", but that suddenly my will is free to chose options that were not available before. And even after I die, my choice to follow Christ on the narrow way means that my options become infinite as I get to spend eternity with the God of infinite choices. Now THAT is good news, news that cures people of despair; news that gives hope and a future to those who are slaves to their choices.

This excites me beyond belief. So, why do we never teach this in our Sunday School?

And what better way to talk about reality than to talk about TV?

And what better way to talk about reality than to talk about TV? I also like Stargate SG-1 and Stargate Atlantis. Yeah, you can say it - I'm a dork. But really, it is pretty mindless and fun television. The charactes are funny, the situations are preposterous, and the humans always win with guns and grenades even though their enemies have force fields and beam weapons. I guess all that military spending during the cold war paid off after all.

I also like Stargate SG-1 and Stargate Atlantis. Yeah, you can say it - I'm a dork. But really, it is pretty mindless and fun television. The charactes are funny, the situations are preposterous, and the humans always win with guns and grenades even though their enemies have force fields and beam weapons. I guess all that military spending during the cold war paid off after all. Speaking of award-winning drama, the new Battlestar Galactica series rocks. You might think you're justified in calling me a double-dork for liking SG-1 AND Battlestar, but you would be wrong. Battlestar Galactica is the West Wing of sci-fi.

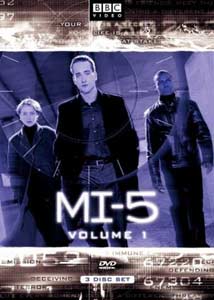

Speaking of award-winning drama, the new Battlestar Galactica series rocks. You might think you're justified in calling me a double-dork for liking SG-1 AND Battlestar, but you would be wrong. Battlestar Galactica is the West Wing of sci-fi. And last, but not least, is MI-5. This show is produced by the BBC, and is about the British version of the FBI. While the series starts out slow (it picks up after a few episodes) and is rather low budget, I think that it ulitmately satisfies.

And last, but not least, is MI-5. This show is produced by the BBC, and is about the British version of the FBI. While the series starts out slow (it picks up after a few episodes) and is rather low budget, I think that it ulitmately satisfies.