Theosis and Love

Maunday Thursday is the day Christians remember the command Jesus gave to the disciples at the last supper: "A new command I give to you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another."

There is a long tradition in Christianity of something called theosis - which means "making divine". Essentially, the idea is that participation within the love of Christ - of loving others as he loved us - causes us to become god-like.

Most of the Christians I know get uncomfortable when I talk about theosis - of becoming divine, but the earliest theologians of the church thought theosis is a very important part of understanding what Christianity is about. They said crazy stuff like:

"God became human so humans would become gods." (Athanasius, 4th Century)

"...the Word of God, our Lord Jesus Christ, who did, through his transcendent love, became what we are, that he might bring to us even what He is Himself." (Iranaeus, 2nd Century)

I suspect the discomfort with theosis is because the idea of human divinity seems like blasphemy. Humans instead should be relegated to distorted and corrupt creatures. But what would happen if we began to take the teachings of these early church fathers seriously - that Christ brought to us what He is Himself, and heals our wounds as part of the forgiveness we are offered?

No early church father seriously thought that we would become God. But they did believe we would become divine. St. John of the Cross puts it best, "[We become divine] not because the soul will come to have the capacity of God, for that is impossible; but because all that it is will become like to God, for which cause it will be called, and will be, God by participation." (16th Century)

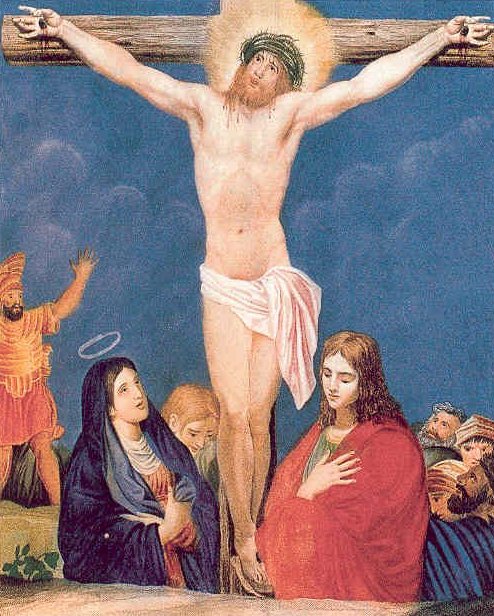

Maunday Thursday reminds us that we are God by participation. That we love as Christ loved. That we sacrifice ourselves as Christ sacrificed. That we take up our Cross, being the vandalized images of God that we are, and look forward to our rebirth as divine creatures. We are called, with this command to love, to be God by participation.